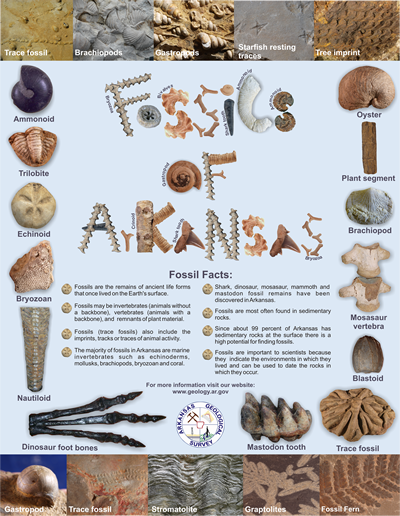

Fossils

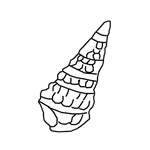

Fossils are the remains of once-living organisms – plants and animals. Animals usually had hard parts such as teeth, bone or a shell that has been preserved in the rock we see today. If the animal had a backbone the fossil would be in the vertebrate category because we would mostly find the fossil bones or teeth of those animals. If the animal had a shell with soft body parts but no backbone then that fossil would be classified as an invertebrate fossil. The majority of fossils found in Arkansas are invertebrate fossils.

Fossils can also consist of leaf imprints or fossil tree sections (such as trunks, roots or branches). In some rocks only the tracks, burrows and trails or traces of the animal were preserved. Plant fossils and trace fossils are included on the invertebrate fossil page.

All of the fossils mentioned thus far are considered macrofossils or fossils that can be seen with the naked eye. The rocks in Arkansas also contain microfossils or fossils that can only be seen with the aid of a microscope. Only macrofossils will be discussed herein. This is meant to be an introduction to the common fossils that may be found in Arkansas with pictures to use as an identification tool.

If you need more assistance to identify a fossil, feel free to email angela.chandler@arkansas.gov or bill.prior@arkansas.gov.

Vertebrate Fossils

Compared to invertebrates, vertebrates are rare in the fossil record. Fossil bones are occasionally found in Cretaceous deposits of southwestern Arkansas where several extinct marine reptiles such as mosasaurs and dinosaurs have been discovered. Pleistocene age deposits (gravels, sinkhole fillings, and caves) have yielded mastodon and mammoth teeth and a variety of mammal bones.

By far the most common record of vertebrates is fossil teeth since these are the hardest parts of vertebrates. Shark teeth have been reported from several Paleozoic formations as well as from the Cretaceous and Tertiary formations. Whale and fish bones along with land mammals and reptiles are present in Tertiary deposits.

Click on the topics below to learn about vertebrates in Arkansas.

- Shark teeth and rays

- Mosasaurs and plesiosaurs

- Dinosaur bones

- Fish bones

- Ice-age mammals

Pseudofossils

There are many features in rocks that appear to be fossils when they are really not. Such features or rocks are called pseudofossils - a natural object, structure or mineral of inorganic origin that may resemble or be mistaken for a fossil (Glossary of Geology, 1989). Some of the more common pseudofossils are listed below.

Concretions and Nodules

Septarian concretions, which may vary in size, are characterized by an irregular polygonal pattern of cracks that are filled or partly filled by crystalline minerals, usually calcite. Its origin involves the formation of an aluminous gel, case hardening of the exterior, shrinkage cracking due to dehydration of the colloidal mass in the interior, and vein filling (Glossary of Geology, 1987). Concretions of this type are present in the Fayetteville Formation in northern Arkansas.

Septarian concretions are sometimes mistaken for fossilized turtle shells

This chert nodule may be mistaken to be a fossilized egg

This chert nodule may be mistaken to be a fossilized egg

Chert nodules are essentially pure microcrystalline quartz that are lenticular or spheroidal in shape and generally found in limestone or dolostone. They may be widely scattered or form continuous or discontinuous irregular beds in the rock. The nodules can be concentrically banded or mottled and may have an outer rind. The chert varies in color from white, brown, black or various shades of gray. These chert nodules were collected from the Boone Formation in northwestern Arkansas. Chert nodules are also present in the Cotter Formation.

Solution Features

Solutioning is a process of chemical weathering by which mineral and rock material passes into solution. An example is the removal of the calcium carbonate in limestone by rainwater. Rainwater is acidic because it dissolves carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

Solution features such as these are usually found in limestones in north Arkansas. Limestones are easily dissolved by the action of rain and groundwater which leaves pits, depressions, and small pinnacles in the rock. The limestone formations in north Arkansas were deposited from the Ordovician through the Pennsylvanian Periods of geologic time. This was between approximately 300 to 460 million years ago a long before the age of man. These features are present in the Ordovician Plattin Limestone.

The features in this weathered outcrop could be mistaken for human footprints (see picture).

This is another example of solutioning (see previous picture write-up) on a limestone in northern Arkansas. This feature was seen in the Fernvale Limestone which formed approximately 440 million years ago. This rock formation formed long before the age of dinosaurs, approximately 240 to 65 million years ago. Therefore, we would not expect any dinosaur tracks or other remains to be found in this part of the state.

Solutioning of this piece of limestone has carved this interesting shape. Note the scalloped edges which are typical of solution features in limestones. This piece of limestone is from the Boone Formation which formed around 340 million years ago, long before the age of dinosaurs.

The feature in this limestone could be misidentified as a dinosaur footprint

This piece of limestone could be mistaken for a dinosaur bone

Weathering Phenomena

The exact processes that create "turtle rocks" are poorly understood. One explanation involves spheroidal weathering. This process occurs when water, percolating through cracks and between individual grains in the rock, loosens and separates layers of the rock. The weathering acts more rapidly on the corners and edges of the rock producing a rounded shape. The weathering of the rocks is also strongly influenced by the polygonal joint pattern seen in all "turtle rocks".

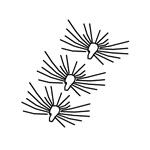

Box-shaped, triangular, and round patterns are abundant in the sandstones of Arkansas. These patterns form when iron present in the rock is oxidized. Iron exists in the minerals pyrite, siderite, magnetite, and hematite. Any of these minerals could be present in sandstone. Early in the formation of the rock, water filled the pore spaces between the sand grains and came into contact with iron-rich minerals. This caused the iron to go into solution. As the rock became exposed to air or fresh water, oxygen was added to the solution. This caused the iron to oxidize and precipitate along exposed joints or bedding planes in the rock formation. Sometimes color bands result from the different oxidation states of iron. These bands are also referred to as liesegang banding or box-work by the scientific community. Often the iron bands form interesting polygonal shapes sometimes referred to as "carpet rock". Other liesegang shapes consist of concentric layers of iron bands which may be mistaken for petrified trees (see picture below).

These rocks are called "turtle rocks" because they resemble the shells of turtles

Carpet rocks

Liesegang banding in sandstone from northern Arkansas

Dendrites

A dendrite is a surficial mineral deposit of an oxide of manganese that has crystallized in a branching pattern (Glossary of Geology, 1987). Dendrites may also consist of iron oxides and other minerals. They could be misidentified as fossils since the branching pattern resembles leaves.

Manganese dendrites in novaculite

Manganese dendrites in novaculite

Pyrite dendrites on Cretaceous limestone